Fidel Castro's Supercow

In the city of Nueva Gerona there stands a white stone statue of one of the most beloved Cuban revolutionaries, whose legacy lives on to this day. But this is not a monument to Che Guevara or Fidel Castro; no, this is a statue of Ubre Blanca. Ubre Blanca was an unusual revolutionary. For one thing, she was female, a tough position in patriarchal Cuba. For another, and, perhaps more notably, she was a cow.

Fidel Castro is one of history’s more polarising leaders. While less inclined to mass murder than many other dictators, he was still an autocrat, and, like most autocratic leaders, he had a grand vision that he wanted to achieve for his country. And that vision was milk. Enough milk to fill the Havana Bay.

The thing is that Fidel Castro loved dairy. Really loved it. He was so famed for it that the CIA once attempted to poison his milkshake. He also almost caused a falling out with the French by demanding that their ambassador say Cuban cheese was better than camembert, which reportedly ended with the ambassador banging the table and shouting “never!” (the French are sensitive about their cheese).

Of course, lots of people like milk. However, most people aren’t unquestioned demagogues of a country with an agrarian economy who can command their top scientists to breed a new species of cow that will produce four times the amount of milk as a normal cow. Which is exactly what Castro did in the 1960s. Cuba at that time was suffering from food shortages, and Castro became convinced that a herd of supercows that could produce huge quantities of milk would be the answer. Unfortunately, the Cuban bovine population wasn’t exactly up to the task, historically having been bred for meat, with milk not being a huge part of the Cuban diet. So Castro told his scientists to create his supercow, using artificial insemination to combine the hardiness of the Cebu with the high yields of the Holstein. “It means that a Cebu cow which produces 1.5 litres of milk can bear a calf that can produce 8 or 10 litres,” he explained in the 1966 speech announcing his new breeding program. “It means that these cows will bear calves in 1967. In 1969, they will be serviced. If in 1970 we have approximately 400,000 cows, in 1971, they will multiply to nearly one million more.” You might call it…(drum roll, please)…cowmunism.

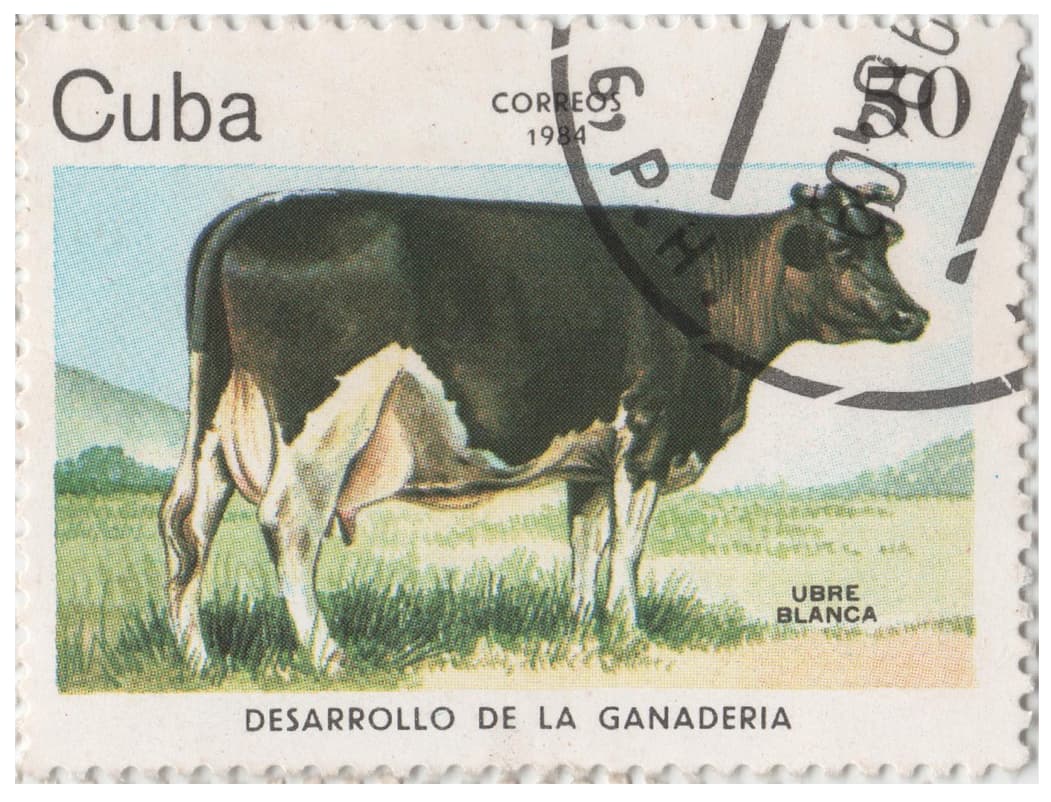

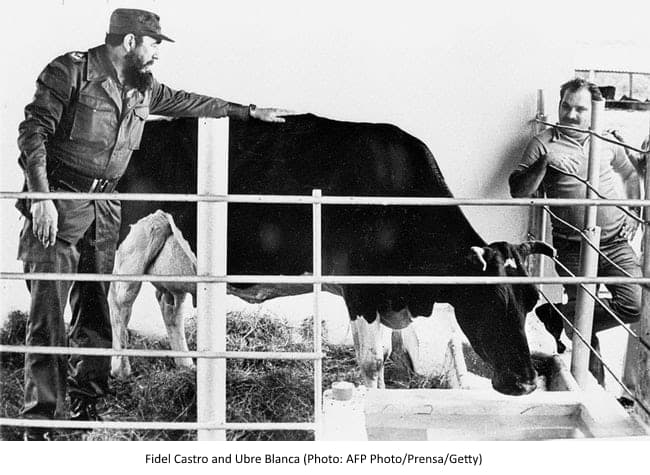

It was a grand vision, but one with mixed results. Of the million supercows Castro had hoped for, they managed to breed a grand total of…one. Ubre Blanca, which means White Udder in Spanish, was the only success story of the breeding program. But what an exception she was. Born in 1972, Ubre Blanca was a milk machine, breaking the world record in 1982 when she produced 109.5 litres of milk in a single day, and then set another record when it was calculated she had yielded 24,269 litres over a 305-day lactation cycle. Castro was thrilled, and not entirely without reason, as Ubre Blanca was producing four times as much milk as a regular cow every day. This proved to be a great propaganda piece, evidence of the efficiency of the communist system and a slap in the face for America. Ubre Blanca was lionised in the Cuban media – they even put her on a stamp.

Being the supercow, Ubre Blanca was treated like royalty. She was kept in an air conditioned stable and had a regular staff on hand to make sure she was comfortable, going so far as to play soothing music during milking. Her food was even tested on other cows before she was given it, lest some assassin should try to poison her.

Being the supercow, Ubre Blanca was treated like royalty. She was kept in an air conditioned stable and had a regular staff on hand to make sure she was comfortable, going so far as to play soothing music during milking. Her food was even tested on other cows before she was given it, lest some assassin should try to poison her.

In 1985, after her third pregnancy resulted in a worrying proliferation of glandular tissue, veterinary surgeons extracted some of her eggs to freeze for future research. Unfortunately, this inadvertently made things worse by aggravating a tumour. Realising her condition was terminal, the vets reluctantly euthanized her a few weeks later. Castro was distraught. He ordered that the cow be given military honours, a full-page obituary in the state newspaper and a heartfelt eulogy from the poet laureate, while the country’s most popular musicians wrote songs celebrating her. Her body was embalmed and put on permanent display at the National Cattle Health Centre near Havana, not unlike the way Lenin’s was in his mausoleum in Moscow.

Unfortunately for Castro, Darwinism failed him. None of Ubre Blanca’s calves inherited her milk producing power. By the late 80s international communism was stalling badly. The Soviet Union, in terminal decline, stopped funding their Caribbean ally, and Cuba’s own economy was flatlining anyway. Milk, far from flowing freely enough to fill the Havana Bay, was now so scarce it was only rationed out to children and pregnant women.

Unfortunately for Castro, Darwinism failed him. None of Ubre Blanca’s calves inherited her milk producing power. By the late 80s international communism was stalling badly. The Soviet Union, in terminal decline, stopped funding their Caribbean ally, and Cuba’s own economy was flatlining anyway. Milk, far from flowing freely enough to fill the Havana Bay, was now so scarce it was only rationed out to children and pregnant women.

In 1993, Castro was reportedly inspired by the movie Jurassic Park to begin attempts to clone Ubre Blanca from DNA samples in a last effort to save his dream. This may have led some to wonder if Cuba was about to be overrun with man-eating cows, but the real outcome was more mundane: the experiments failed and were abandoned shortly afterwards. That year, Cuba reluctantly accepted US donations of food, medicines and cash, and a system of private farmers’ markets was set up in 1994 to provide easy access to locally grown food. Cuban communism effectively died with Ubre Blanca.

The place of animals in politics did not die with Ubre Blanca, however – or indeed begin with her. Animals have proven quite crucial in diplomatic relations for many years. In 1961, at the height of the Cold War, Nikita Khrushchev gave JFK a puppy called Pushinka. Despite being a sly dig at the Americans – Pushinka was the offspring of Strelka, who had been sent into orbit aboard Korabl-Sputnik 2 in 1960, a huge propaganda victory for the Soviets – the gift did serve to maintain a semi-friendly relation between the rival superpowers, raising the interesting prospect that a puppy may have helped avert nuclear war. Soviet space dogs were highly exploited for propaganda, as can be seen from this Romanian stamp from 1959:

Animal diplomacy has become ubiquitous. Chinese leader Mao Zedong, apparently unbothered by the thought of stereotyping, gifted a pair of pandas to the US in 1972 after President Nixon visited Beijing. Ted Heath then made things awkward by asking why he didn’t also get some pandas, so the Chinese duly sent two to the UK in 1974. In fact, from 1958 to 1982, China gave 23 pandas to nine different countries.

Animal diplomacy has become ubiquitous. Chinese leader Mao Zedong, apparently unbothered by the thought of stereotyping, gifted a pair of pandas to the US in 1972 after President Nixon visited Beijing. Ted Heath then made things awkward by asking why he didn’t also get some pandas, so the Chinese duly sent two to the UK in 1974. In fact, from 1958 to 1982, China gave 23 pandas to nine different countries.

In 1990, the Indonesian president opted for something less cuddly when he gave George H.W. Bush a Komodo dragon. The dragon was sent to the Cincinnati Zoo, where it produced 32 offspring before passing away in 2004. In 1993 the president of Turkmenistan gave British PM John Major a pure-bred stallion – the British ambassador to Moscow had to arrange transport from Ashgabat to the UK. In 2006, Bulgarian President Georgi Purvanov gave George W. Bush a puppy. In the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, five Chinese sturgeons, symbolising the five Olympic rings, were given by China’s Communist Party to Hong Kong.

In 2014 at the G-20 Summit in Brisbane, koala bears were part of a diplomatic campaign where several world leaders took turns holding the cuddly critters (because the Aussies also don’t care about stereotypes). Mongolia likes giving people horses, with South Korean President Park Geun-hye, Vice President of India Mohammad Hamid Ansari, Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi, and the United States Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel all receiving one. Queen Elizabeth II has been given many animal gifts, including a pair of sloths from Brazil and a male elephant named Jumbo from the Cameroon government.

The animal diplomacy doesn’t always go according to plan, however. In gratitude for France’s assistance in driving out Islamist militants in 2013, Mali’s government gave president François Hollande a camel. Deciding there was no room for it at the Elysée Palace, he left it in the care of a Timbuktu family – only to discover they had cooked it in a tagine. The embarrassed Malians promptly gave Hollande “a bigger and better-looking camel”. In 2016, a minor diplomatic row emerged after Vladimir Putin declined to accept a dog presented to him by the Japanese prime minister. On the eve of a summit between the two powers, Japan’s Shinzo Abe wanted to give the Russian leader a male partner for a female Akita called Yume, which Japan had gifted to Putin in 2012. Putin suggested he simply didn’t want another dog, although many commentators said it was likely a deliberate snub. Putin has also been accused of attempting to intimidate Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, when he let his large black Labrador into one of their first meetings in 2007, as Merkel is afraid of dogs.

Not all German leaders have taken such a dim view of dogs. While happily overseeing genocide and war on an unprecedented scale, Adolf Hitler was an animal loving vegetarian who implemented some of the world’s first anti-cruelty legislation (although ordering medical experiments to be carried out on humans instead of animals isn’t going to win you Good Guy of the year). His secretary reported that the only time she ever saw the Führer cry was when he poisoned his German Shepard, Blondi, just before he killed himself, for fear she would be mistreated by the Russians that were closing in on Berlin. It’s a strange character trait for a man whose name had become synonymous with unrestrained evil.

Yet Hitler isn’t an anomaly. Many notorious tyrants have had an unexpected soft spot for animals. While still a Marxist revolutionary in exile, future Soviet despot Joseph Stalin had a dog called Tishka which he joked made a better political debating partner than most of the Bolsheviks (and Tishka was never sent to die in a gulag, unlike most of the Bolsheviks). Stalin’s predecessor, Vladimir Lenin, had a cat – for some reason, the cat’s name has become the source of heated discussion on the internet (Chairman Meow is arguably the best answer, albeit one that would have made no sense chronologically or linguistically). The insane Roman Emperor Nero liked his horse so much that he made it a consul, the highest political position in the empire. Kim Jong-il, the former North Korean leader, was devoted to his French poodles, reportedly importing fancy dog shampoos and high-quality beef for them while millions of his people starved. On one occasion, some of the diminutive dictator’s malnourished staff were sent to a prison camp after being caught eating some of the beef themselves. The love of dogs apparently runs in the family: Kim’s son and heir, the equally unpalatable Kim Jong-un, opened a “dog zoo” in Pyongyang.

But why do the worlds of politics and animals cross so much? Is it just a random quirk, or is there something more behind it? Well, when you think about it, there is method in the madness. Animals have been inextricably tied to human culture since cavemen painted pictures of mammoths on their walls. Most early civilisations based their gods and myths on animals, and many ancient empires had mythological origin stories involving animals. The supposed founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, were said to have been raised by a wolf. The Aztecs believed their city of Tenochtitlan had been founded when the nomadic tribes were signalled by an eagle eating a snake perched atop a cactus to start building in that place, a legend immortalised on modern Mexico’s flag. You might be fond of cats, but the Ancient Egyptians literally worshiped them as incarnations of their gods. Even secular histories invoke animal imagery. The bald eagle dominates the Great Seal of the United States, a deliberate attempt to mimic the eagle emblems that adorned artwork of the Roman Republic, whose prowess the American revolutionaries hoped to imitate. It is hard to think of any civilisation that has not woven animals as totems into their culture. When this is considered, it becomes clearer why giving animal gifts is such a popular theme. Giving an animal that is representative of your culture has been a diplomatic strategy since people still lived in tribes, and like may traditions it persists to this day precisely because it’s always worked. By their very nature of being apolitical, animals work as a fantastic bridge between two cultures. They help to undercut harsh political rhetoric by refocusing attention away from controversial issues, and in the modern world can unite people around shared concerns of conservation and sustainability. Without them, we’d probably have nuked ourselves into oblivion by now.